In her doctoral thesis, Kate Hawley has studied the sea trout in the Norwegian Sognefjord, which is significantly affected by human activities. As a result, fewer fish are venturing out into the open sea, and most are now migrating shorter distances than before.

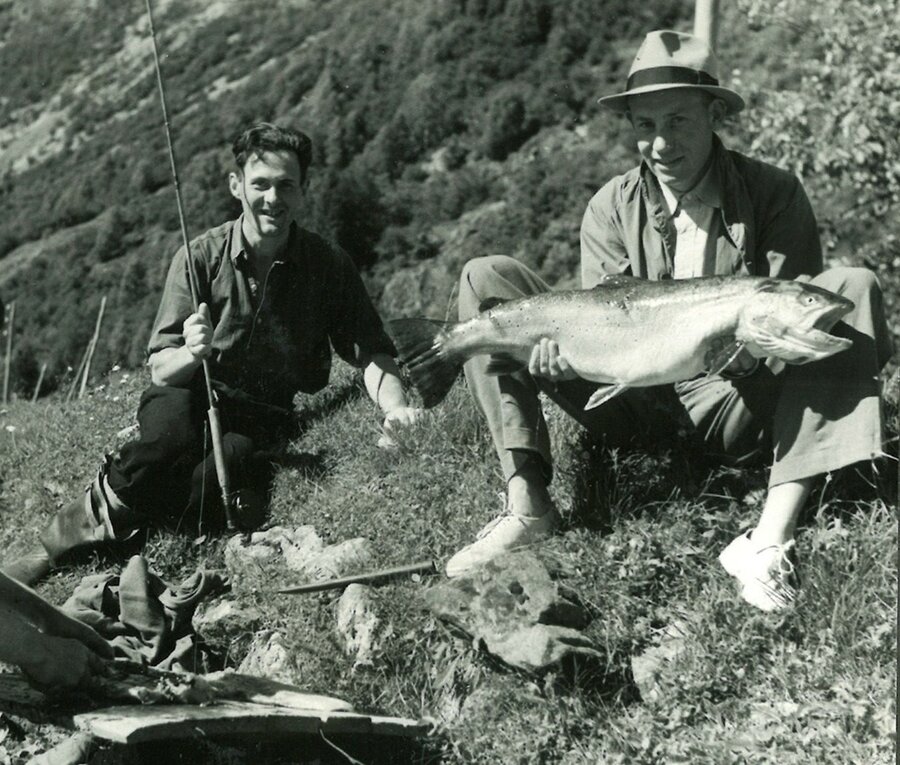

The sea trout in the Sognefjord represents an important socio-economic resource, and the fjord has a rich fishing history. Several of the fjord’s rivers are known for both salmon and trout fishing, with Lærdalselva and Aurlandselva being the largest. Sea trout is a type of trout that migrates from freshwater to fjord and coastal areas to grow large on rich marine resources. This journey is fraught with risks for the fish.

“These trout populations are under increasing pressure from human influences,” says PhD candidate Kate Hawley.

Tracked Trout in the Sognefjord

Recently, the development of salmon farming and hydropower, as well as fishing, has increased in scope. Despite the Sognefjord being protected from human activity through the management scheme “National Salmon Fjords,” the trout in the fjord are significantly affected by sea lice from salmon farming.

In her doctoral research, Hawley has investigated whether these human factors have led to the sea trout becoming a less favored ecotype. She has equipped sea trout in the Sognefjord with acoustic transmitters and tracked their migrations between freshwater and the fjord over several years, as well as conducted genetic analyses.

More lice, higher mortality

Hawley’s results showed that trout swimming from the rivers at the innermost part of the Sognefjord to the coastal areas are the most affected by salmon lice infestations.

“These are the fish that die most from salmon lice,” she says.

During the study period, this lice-related mortality varied between years and populations. However, there is a clear trend between “before” and “after” the introduction of aquaculture and hydropower in the Sognefjord.

“When we compare before and after, there are clear indications that fewer fish are now swimming all the way to the coast,” says Hawley.

Is it worth the long journey?

The fact that fewer fish are willing to make the long journey is a problem.

“It is in the outer fjord areas that sea trout find the nutrient-rich food that allows them to grow large,” she explains.

“Large and strong fish can swim back to the rivers where they need to spawn. There, they lay many large eggs and produce a lot of high-quality offspring.”

However, researchers are now seeing a shift: the majority of sea trout only partially swim out of the fjord before turning back.

“Here, a trade-off is made between gain and risk,” she says.

Hawley has created simulations based on migration models from the tagged sea trout and salmon lice models from the fjord. The analyses show that fish migrating mid-fjord had the best balance between gain and risk. These fish find enough food to produce a certain number of eggs while minimizing the risk of dying.

Returning to other rivers

In her study, Hawley examined five different trout populations. The results showed that in some cases, the fish return to a different river than the one they are genetically from, where they overwinter or spawn.

“When fish spawn in a different river this way, genes mix between populations,” explains Hawley.

This mixing is called gene flow, which increases genetic variability within populations. Gene flow can affect local adaptation to different river environments but can also lead to the overall sea trout population in the Sognefjord gaining increased resilience to human-induced changes.

These results have important implications for the management of fish in the Sognefjord, as the individual populations influence each other and must be viewed as a whole—a metapopulation.

Kate Hawley forsvarer sin avhandling "Anadromi hos aure i antropocen" fredag den 25. oktober, 2024. Prøveforelesning og disputas er åpne for alle - les mer om det her.